Passing the Magic: Horace Tapscott and His Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra

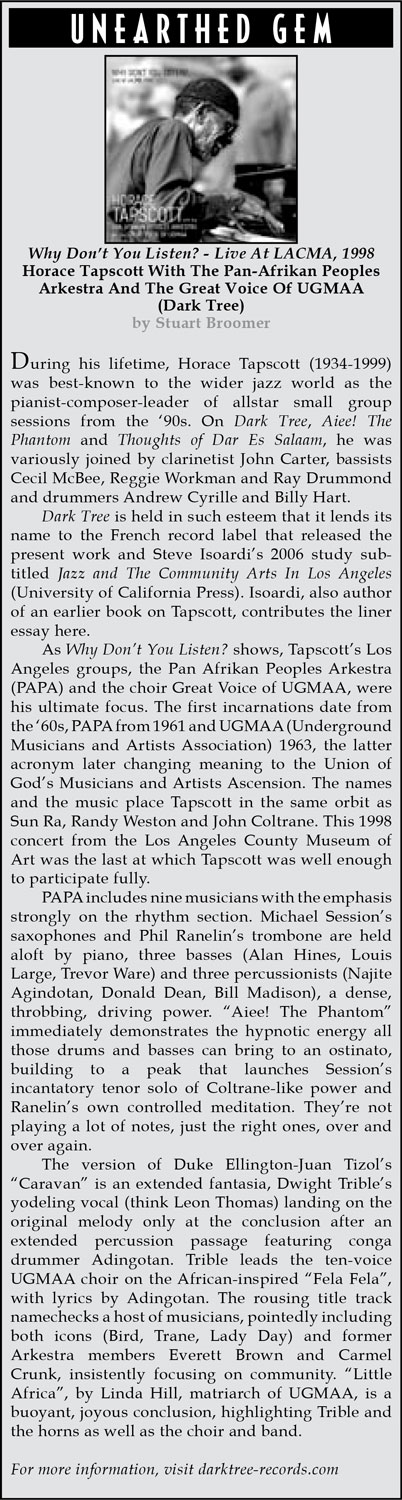

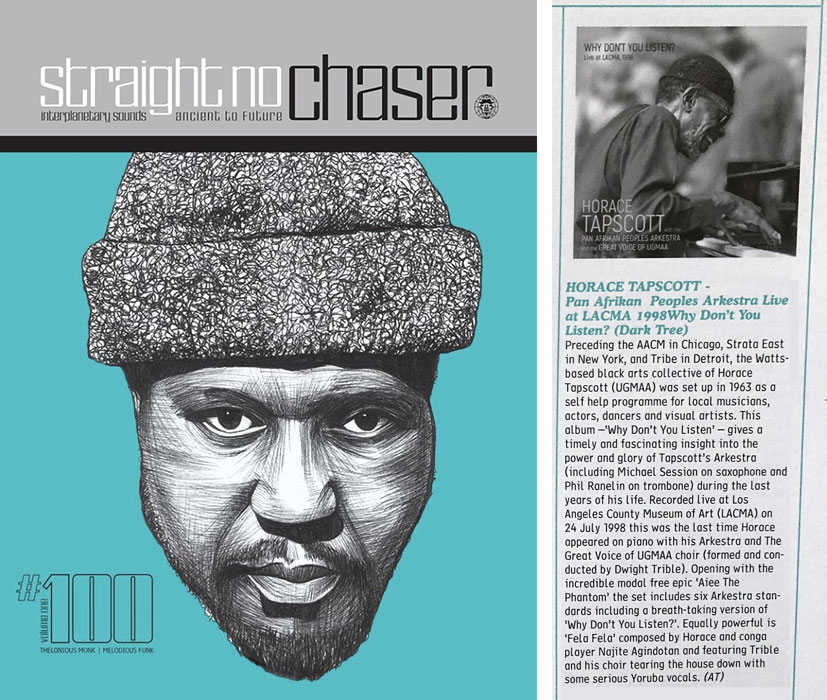

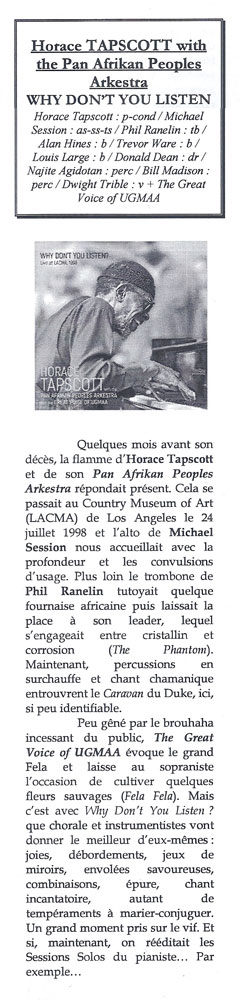

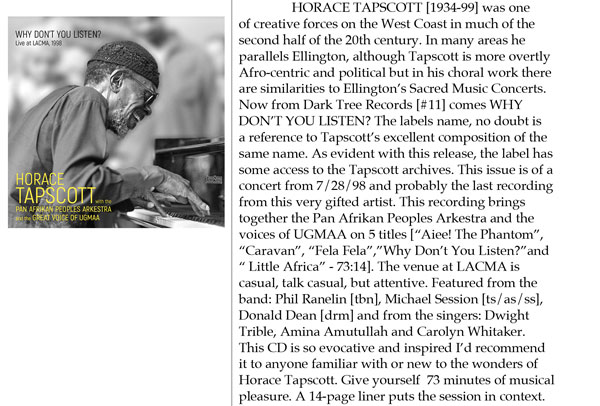

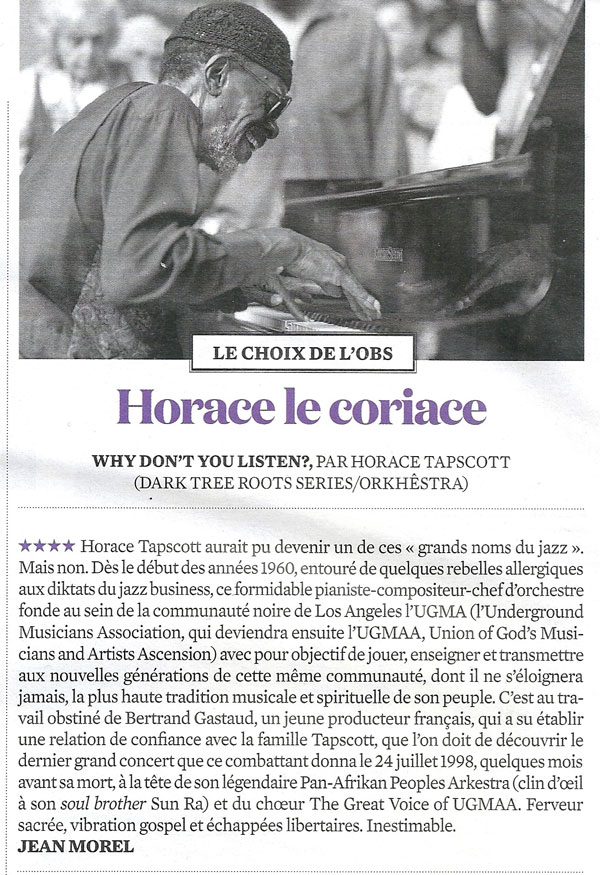

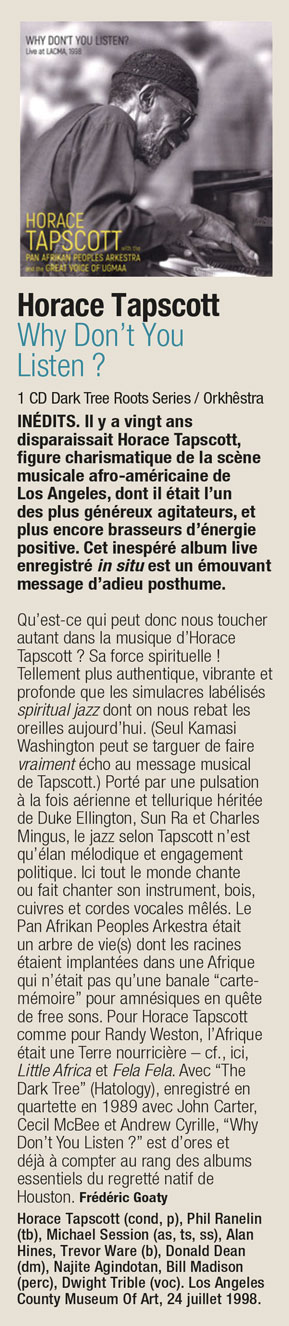

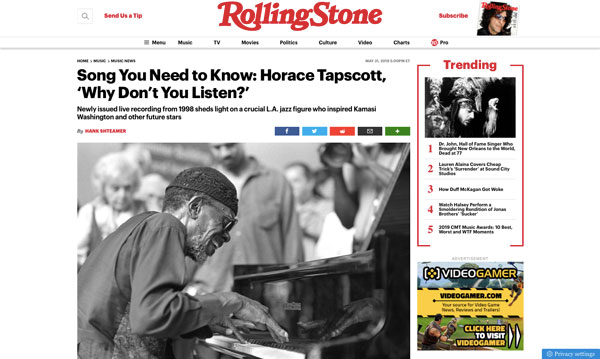

“Why Don’t You Listen?” is a posthumous recording released in May 2019 on Dark Tree Records by the Los Angeles pianist and community artist Horace Tapscott. Though Tapscott died in 1999, his legacy burns brighter than ever because of the rising popularity of contemporary jazz artists like Kamasi Washington. The new release was recorded live at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on July 24th, 1998, and it was one of Tapscott’s last performances before he passed. The five songs on the record are quintessential transcendental Tapscott accompanied by his Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (Ark).

As this record testifies to, Tapscott and his Ark is the source of so many movements that continue to this day. In addition to his incredible music, Tapscott’s status is further bolstered by his integrity and how he lived his life. Though the man was an enormous talent on piano, early in his career, he decided that leading a community orchestra was a bigger priority than his solo success.

Tapscott’s biographer, Steve Isoardi, writes in the record’s liner notes: “Today, the new label emerging for the music from Los Angeles’ black community has become ‘spiritual jazz.’ For Horace, the Ark, the choir and the many brothers and sisters whose roots stretch back decades, their art was also community, political and revolutionary. In essence, an active opposition to all manifestations of oppression — spirituality at its most meaningful.”

Whatever label you want to call the music, every note in the recording trumpets freedom and truth. The five songs create a mesmerizing tapestry of sound and have a timeless essence that provokes a call to action.

The Roots of the Ark

Born in Houston, Texas in 1934, Horace Tapscott moved to Los Angeles in 1943 because his stepfather got a job in the then-booming defense industry. 1943 was one of the biggest years in the Great Migration, and Los Angeles’ black population nearly doubled in the 1940s. Tapscott moved into South Central, right off the famed Central Avenue Jazz Corridor. Sooner than later he was studying with two of the best music teachers in the city.

At Lafayette Junior High School, he studied with Percy McDavid. McDavid encouraged students to write their own music and to study the fundamentals. “Mr. McDavid,” Tapscott says in his autobiography, “Songs of the Unsung,” “also had a band that played in different parks around the city every Sunday. He had Charlie Mingus, Britt Woodman, Eric Dolphy, Buddy Collette, Red Callender and John ‘Streamline’ Ewing. All the cats were in it.”

McDavid’s band not only had all of these future jazz greats, but McDavid was close with the pioneering black composer William Grant Still and the music teacher from Jefferson High School, Samuel Browne. Sooner than later, Tapscott would regularly be playing events around Central Avenue with the aforementioned artists, as well as McDavid, Browne and other stalwart musicians like Gerald Wilson. Tapscott grew up with them all.

By the time Tapscott got to Jefferson, he was writing his own music and was already close with Samuel Browne. Browne was an exceptional pianist and, in 1936, was also the first black male teacher hired in the Los Angeles Unified School District. He had graduated from USC and had gone to Jefferson himself a decade before he taught there. Similar to McDavid, Browne was close friends with many of the musical heavyweights, and it was an everyday occurrence for someone like Duke Ellington or Lionel Hampton to come by class and talk with the students. Browne was keen on sharing the tradition and exposing his students to the best musicians.

“All the musicians would come pick you up, the young cats, take you to rehearsal, and bring you back home,” he said in “Songs of the Unsung.” “You’d come out of the house, and there was a well-known, world-renowned trumpet player waiting to take you to rehearsal. They were always looking out for you, and they were serious; they wanted you to learn. All the time you were riding with them, they’re talking, and they’re jamming with you.” Tapscott carried the same process of mentoring when he was older, inculcating these values and technical skills to younger artists. Moreover, he remained close with Samuel Browne his entire life, all the way until Browne passed in 1991.

Tapscott picked it all up quick and never forgot the fundamentals. Throughout his career, he and the Arkestra would often play at least one or two cover songs in their live sets. The second song on the new record, “Caravan” is a famous Duke Ellington composition played flawlessly by Tapscott and the Arkestra.

These early years set the table for Tapscott’s greatness, and also his value system. Under McDavid and Browne’s tutelage, Tapscott cut his teeth playing clubs like Jack’s Basket Room in L.A.’s Central Avenue while he was still in high school. By the time he was in his early 20s, Horace had landed a job playing with Lionel Hampton. After a few years of touring with Hampton, Tapscott decided to quit Hampton’s band and came home to start his “Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra” in 1961.

The Dark Tree

The longer story of Horace and his Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra is told in two books, his autobiography from 2001, “Songs of the Unsung” and “The Dark Tree: Jazz and the Community Arts,” written by author Steve Isoardi and published in 2006. Tapscott’s example is so influential that it even led Michael Balzary, aka Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, to start his own music academy, the Silverlake Conservatory of Music, after he read Tapscott’s life story.

Horace Tapscott never liked the word “jazz.” To him it was black music. In his autobiography he explains, “I wanted to preserve and teach and show and perform the music of black Americans and Pan-Afrikan music, to preserve it by playing it and writing it and taking it to the community. That was what it was about, being part of the community, and that’s the reason I left Hamp’s band that night.” His purposes with the Arkestra were about preserving black music and playing music across the community to educate and uplift everyone, like it did for him.

One of the Ark’s best-known songs, “The Dark Tree,” he explains in his autobiography, “has to do with the tree of life of a race of people that was dark, and everybody went past it and all its history. The whole tree of a civilization was just passed over and left in the dark, but there it stood still.” This concept of “The Dark Tree,” connects directly to his efforts to protect and preserve black music. The idea is so central to Tapscott and the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra that when Steve Isoardi thought about the title for the extended history on the Ark, “The Dark Tree,” was the obvious choice after his partner, the filmmaker Jeannette Lindsay, suggested it to him one day.

While his autobiography tells Tapscott’s life story chronologically, “The Dark Tree” traces Tapscott’s life during his years with the Arkestra. The narrative spotlights the Ark itself and Tapscott’s role as a community artist from his days in high school, through the late 1990s. Over the course of nearly 40 years, well over 300 different musicians played with the Ark at one time or another. Several of the musicians who started early in their careers with the Ark, like Arthur Blythe and Roberto Miranda, went on to further success later on as both solo artists and with different groups.

Isoardi describes the defining spirit of a community artist in the book’s first chapter, “Roots of the Community Artist.” He writes, “To ensure social continuity, artists and musicians took seriously the responsibility of passing along their knowledge and skills to the next generation. This was accomplished primarily through the craft and family structures and through participation in the communal process, involving absorption, adaptation, and imitation.”

Tapscott called it “passing the magic,” after being told at a very young age by Samuel Browne that the only way he was going to be let in on the secret knowledge is if he passed on down the line when he became the teacher.

Tapscott often declared that the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra always had at least three generations on the same stage. Isoardi writes in “The Dark Tree” that “Through this interaction of young and old, inexperienced and talented, the musical tradition was nurtured and passed along.”

Why Don’t You Listen?

If there’s one song on “Why Don’t You Listen?” that explicitly vocalizes Tapscott’s values it’s the title track. Originally written in the 1960s by Horace with lyrics co-authored by his longtime collaborator Linda Hill, the song repeatedly asks, “Why don’t you listen?” The chorus of singers asks in the song:

Why don’t you listen to sounds of truth

Why don’t you listen

Why didn’t you listen to Bird and Trane

Why didn’t you listen

Why didn’t you listen to Lady Day

Why didn’t you listen

Why didn’t you listen to what they say

Why didn’t you listen

Throughout the song’s six verses there are different names of musicians and community members called out. The question is asked again and again, “Why don’t you listen?” Names like Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, Thelonious Monk, Dinah Washington and several others, are called within the litany. The song speeds up and slows down, pulling the listener in closer and closer through every cycle. For Horace, the music is a communion. He always wanted people to listen to the musicians, listen to the poets and listen to members of the community. At one of the most climactic sections of the song, the choir sings, “now listen,” followed by a pregnant pause.

A buoyant socio-political spirit is a driving force in all of his music, and this track especially epitomizes the energy. The radical musicality ever-present in performances by the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra is why they were the group of choice for the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panthers during the late 1960s.

The Arkestra at Full Strength

Tapscott’s Arkestra is in rare form on this recording, and what makes it extra special is that though the group had an almost 40-year history of playing events, they only recorded a few albums. They were never focused on commercial success; they were too busy playing music at public parks, schools, churches, prisons and anywhere else they were called. “We did a lot of things in the community that we didn’t advertise because it was done just for the community,” Tapscott says in his autobiography.

What also makes this recording extra valuable is that it is with the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra in its expanded format and last concert at full strength. Tapscott played in only three more shows after this, but two of them were with smaller groups. The Ark only played one more show with Horace, in September 1998, at the Leimert Park Jazz Festival, and his arm was in a sling. Footage from this final concert is featured in the documentary, “Leimert Park: The Story of a Village in South Central Los Angeles.” “You can see Horace at the beginning of the film with his arm in a sling,” Isoardi says. “Yet, by the closing segment, when they are doing ‘Little Africa,’ his arm is out of the sling as he conducts. The power of the music!”

Tapscott would often play a trio or quintet at the museum’s frequent Friday concerts, but this time, according to Isoardi’s breakdown in the liner notes, Tapscott “decided to stretch beyond the usual small group format by bringing in the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (Ark), nine members strong, including three bassists (he always loved a strong bottom sound), and The Great Voice of UGMAA (Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension), an ensemble of 12 voices, including Amina Amatullah, a veteran of their first choir formed in the 1960s” (for a complete list of all the players and choir members see the notes on the sidebar).

The 12 voices of the choir were led by vocalist Dwight Trible, who is still actively recording today. Listening to Trible sing in songs like the third track, “Fela, Fela,” it’s easy to see why some have called it “spiritual jazz.” “Fela, Fela,” is of course in honor of the great Nigerian Afrobeat artist Fela Kuti who Tapscott admired but never had a chance to meet. This tribute track was only performed live on four occasions. It’s a collaboration Tapscott created with the Arkestra conguero Najite Agindotan, who in his early years had been around Fela in Nigeria before he moved to America.

Najite told Isoardi that Tapscott took the horn line from the iconic Fela song, “Why Black Men Dey Suffer,” and reinterpreted it on piano. “He sat on the piano and took the horn line I put to song to a different height. He blew my mind,” Najite exclaims. The blend of piano, heavy bass, drums, horns and chorus of voices cascading creates a soundscape of music that defies words.

The Phantom

The opening track, “Aiee! The Phantom,” features some of Tapscott’s trickiest piano work. The song, Isoardi writes in “The Dark Tree,” is “based on a piece Horace composed in the early 1970s for the film ‘Sweet Jesus, Preacher Man,’ (and) was a reference to an image that had come to be associated with him, a reflection of his bohemian, underground reputation and his penchant for late-night ramblings, his sudden visits to friends and music venues and abrupt disappearances.” Tapscott was a phantom in multiple ways. Musically, because he was so quick on the keys, and also because he was elusive and would suddenly appear out of nowhere.

In this way, Tapscott was like a superhero that appeared and disappeared both musically and in the physical realm. The song, “Aiee! The Phantom,” emulates Tapscott’s spirit with his piano playing appearing and disappearing in a sort of dance between the horns, bass and drums. It’s easy to see how the original composition was used for a film.

The Final Song on the Album: ‘Little Africa’

“Little Africa,” is the final song on the album, and according to Steve Isoardi, it was written by Linda Hill in the mid-1960s in honor of her new grandson. If Horace was the father, or Papa, of the Ark, Linda Hill was the mother. She was involved with the Ark for many years. “Horace and the Arkestra performed ‘Little Africa’ for decades,” Isoardi tells me. “Over the last ten years of Horace’s life, ‘Little Africa’ became his preferred way of closing concerts, with ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing,’ the ‘Negro National Anthem’ as a two-line coda.”

The song is especially important to the Ark’s oeuvre because it resonates on many levels with the Arkestra, politically and personally. “When one of the first vocalists to join the band in the 1960s, Amina Amatullah, returned in the early 1990s at Horace’s urging,” Isoardi remembers, “hearing the piece performed brought tears to her eyes.” It is the perfect song to close out the record.

Horace Tapscott is Not for Sale

The influential Los Angeles Poet Kamau Daaood got his start with the Ark in 1968 when he was 18, at a concert the Ark was playing in South Park on Avalon and East 51st Street. Daaood was sitting in the park with his poems when he was called up on stage. Tapscott became his mentor and in many ways Daaood’s own career has mirrored Tapscott’s. Daaood is now almost 70 years old. When he began, he was the youngest member of the Watts Writers Workshop. Now he’s one of Literary Los Angeles’ elder luminaries, but he never chased the fame.

Over the last 50 years, Daaood has wrote a lot of poetry with the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and throughout the community. He also co-founded the seminal performance space, the World Stage, in 1989. In the Ark, Daaood was known as “the Word Musician.” Peter J. Harris recently told me that Daaood is the best wordsmith he’s ever seen at performing poetry accompanied with music, even better than Amiri Baraka.

One of Daaood’s best known poems, “Papa, the Lean Griot,” pays tribute to Tapscott. Tapscott was called Papa for his obvious fatherly characteristics, but also because this was an acronym for Pan African Peoples Arkestra. Daaood’s poem is printed in both his City Lights book, “The Language of Saxophones” and near the conclusion in the final pages of Tapscott’s biography, “Songs of the Unsung.” The final stanza captures Tapscott with incredible veracity:

I am Horace Tapscott

my fingers are dancing grassroots

I do not fit in form, I create form

my ears are radar charting the whispers of my ancestors

I seek the divinity in outcasts, the richness of rebels

I walk these sacred streets remembering

kola nuts and cowrie shells

and how well our uncles wore their trousers

I am Horace Tapscott

and I am not for sale

There’s a recording of this Daaood poem, but it is not on this new record. Nonetheless, Daaood’s poem captures the spirit of Tapscott incredibly. Tapscott created form carrying on the stories of his ancestors. He also sought the divinity in outcasts and celebrated the richness of rebels. Similar to the old school Oakland Raiders that took castaways from other teams and made them integral pieces of theirs, Tapscott found a way to use everyone’s skills.

William Marshall, a longtime member of the Ark and a well-respected musician and actor, writes in the foreword of Tapscott’s autobiography about memories “where they handed out percussion instruments in wood, hide, metal, and shell to everyone in the audience — adults and children — who wanted to join in, who had something to say and was willing to try to say it, and who held, perhaps for the first time, an instrument with which to begin.”

KCET and the Watts Prophets

Tapscott worked with a number of poets in addition to Kamau Daaood. The first poet that read with the Ark was Jayne Cortez, who was married to Ornette Coleman and eventually moved to New York, where she found more fame. Several other poets read with the Ark, including a few members of the Watts Writers Workshop like Ojenke, Eric Priestley, Quincy Troupe and the Watts Prophets. Richard Dedeaux of the Watts Prophets worked at KCET in the early 1970s and even got Tapscott to write a theme song for the Sue Booker-produced show “Doing It at the Storefront.”

Dedeaux recounted the story to Steve Isoardi in “The Dark Tree.” “There was nothing dealing with black and brown news,” according to Dedeaux. “So they gave us a news and public affairs show. ‘Doing It at the Storefront.’ We moved out of KCET and got a storefront building on Forty-seventh and Broadway, right down the street from the Malcolm X building. Our whole budget was so tight, like $250 a show. So what we did, we sat down and pooled all our money, and we got Horace to write us a theme song for ‘Doing It at the Storefront.’ It’s an incredible song … Man, he sure made the show.”

Longtime aficionados of the Watts Prophets and the Ark speak about this show and the theme song like it’s the long-lost Holy Grail. The concept of focusing on black and brown news used in “Doing It at the Storefront” is also a desperately needed format for 2019.

The Legacy of the Community Arts Movement

Tapscott listened to the community and his fellow musicians. As Daaood said, he was not for sale. He lived an uncompromising life. Though he made some short-term sacrifices like fame and more money up-front, by the end of his career he was internationally known and especially revered because he played by his own rules. Tapscott recounts a story about how when he first met the legendary East Coast artist Horace Silver, Silver told him that he’d been hearing the name Horace Tapscott for 20 years. The integrity in which Tapscott lived is why his music and legacy matter now more than ever.

Tapscott always said that art is contributive and not competitive. When I first heard this in 1998, it changed the trajectory of my own artistic career. Somewhere around April 1998, I saw Tapscott speak at Skylight Books right after “Central Avenue Sounds” was published. He was one of the voices in that seminal book that in many ways kick-started a deeper interest in the history of Central Avenue and black music of Los Angeles. The stories Tapscott shared that day at Skylight inspired me and changed my life forever.

I had recently seen poetry slams and emcee battles where good friends would become adversaries, egos would get in the way and power struggles would unfold while the respective artists would tear each other down. Tapscott’s model of building community showed me that there was another way. He still achieved excellence, but rather than subscribing to a scarcity mindset, he believed there was room for everyone to shine accordingly. Furthermore, he believed in sharing knowledge and passing it on, like Samuel Browne had done for him. These core philosophies of Tapscott became bedrock ideals for me and they have deeply informed my own ethos as a writer, poet, scholar and educator.

“Why Don’t You Listen?” is a quintessential capsule of Tapscott’s music and his message. As people around the world begin to get excited about L.A.’s spiritual jazz community in 2019, there’s never been a better time to listen to the grandfather of the entire scene who kick-started it all over a half century ago.

What’s more is that now more than ever we need to listen to others. We need to listen to the community and the musicians for a new vision. Tapscott’s music was ahead of its time, and we are finally catching up. Moreover, Dark Tree Records will be releasing a few more of their lost recordings in the next few years.

One more final note, the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra continues to play to this day with a combination of some of the elder members and a new group of young, very talented musicians. They are now under the direction of Mekala Session, a young musician who studied Jazz at the California Institute of the Arts and grew up watching the Ark because his father, saxophonist Michael Session, was the leader of the Ark after Horace passed (Michael Session also plays on the record).

The Ark has recently played local events around Los Angeles in spaces like the Zebulon and World Stage. The Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra continues on, and “Why Don’t You Listen?” is the perfect recording to honor its history and simultaneously introduce its work to new listeners. So, in the words of Horace Tapscott, “why don’t you listen?”